True Maine Bush Flying Stories - A Review By BackcountryPilot.Org

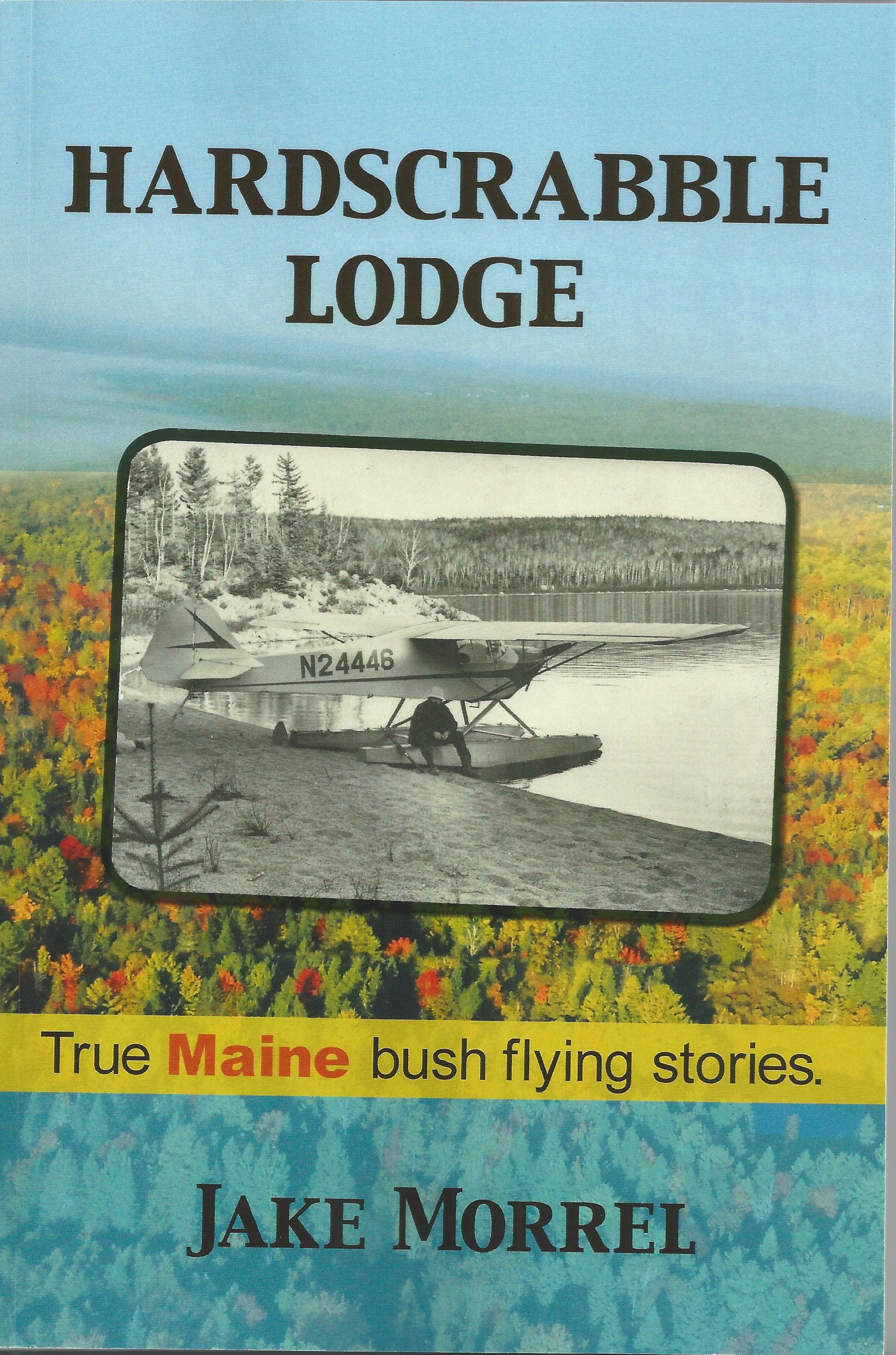

/Pilot and author Jake Morrel has released Hardscrabble Lodge: True Maine Bush Flying Stories, a vivacious and colorful tale of his pursuit of a life in the wilderness of northwest Maine.

By Jake Morrel | September 28, 2016 12:00 am

About the book

Jake Morrel's Hardscrabble Lodge: True Maine Bush Flying Stories is an entertaining read for anyone with a common love for adventure and the promise of the wilderness lifestyle. This great mix of stories chronicling the early days of his flying career, his arrival at Hardscrabble, and many of the humorous anecdotes and near misses from life at the lodge is a worthy addition to the bush flying book collector's shelf.

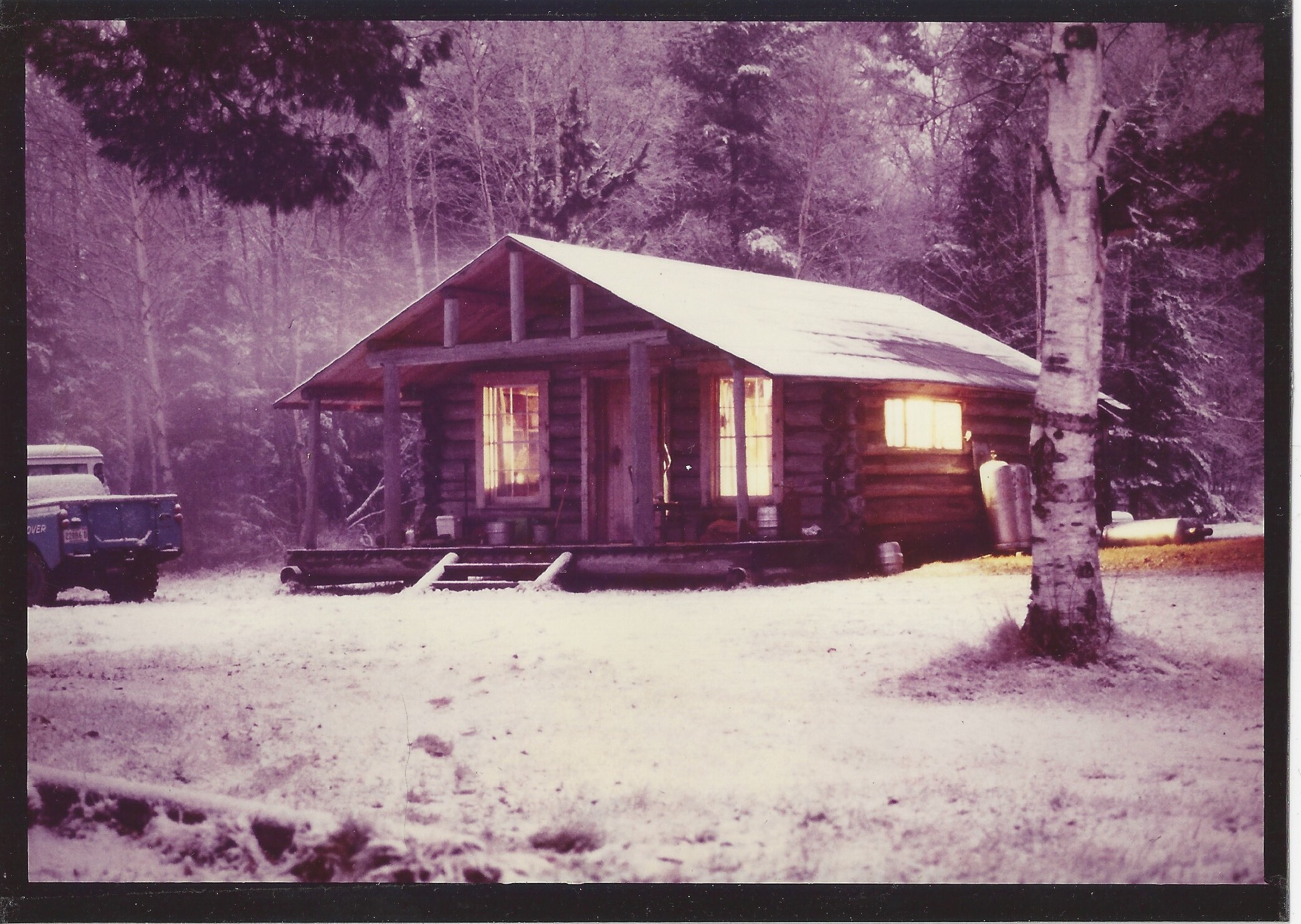

If you're like me, the mere look of a film print from 30, 40, or even 50 years years ago stirs a powerful nostalgia, making it difficult not to think of your parents' or grandparents' time. Jake's old film photos of his Hardscrabble days with family and airplanes is no exception.

What follows is a personal intro from Jake and 2 chapter excerpts from the 167 page paperback book, which can be purchased directly from Maine Authors Publishing for $21.95. —Zane Jacobson, editor@backcountrypilot.org

The dream of Hardscrabble Lodge

Nearly forty years ago, I gave up my dream job as a Part 135 bush pilot in order to buy a dilapidated set of log buildings in Northern Maine, which became Hardscrabble Lodge.

Previously at Folsom’s Air Service, I was lucky to fly nearly new Cessna floatplanes, plus a trusty old DeHavilland Beaver. Every night I returned to the base and always counted on the support of older, more experienced pilots.

Hardscrabble Lodge, on the shore of Spencer Lake.

Young and naïve, I purchased a beat up Super Cub and proceeded to face the challenges inherent in a wilderness operation. In time, gale force winds, mini icebergs and a forest fire would threaten our plane and home. So, why take such a risk and trade a sure thing for likely failure?

As a bush pilot, every several days I ferried guests to and from the numerous established lodges north of Greenville. Listening to the banter of outbound guests caused me to imagine my family living in the woods. After staying several nights as a lodge guest, during company parties, the concept became an obsession. Only one major obstacle blocked the road: money!

The Morrel kids posing with a glorious firewood reserve.

Successful lodges rarely sold and when that happened the prices were enormous, way beyond our means. The only path forward was to start from scratch and build both the buildings and the business. So we powered ahead. I know now that our chances of success were nearly zero. Why the bank lent me money is a mystery! However, blessed with the most incredible good luck one can imagine, we created Hardscrabble.

The following are two short chapter excerpts which illustrate the perils of that journey.

Chapter 5: Plane liftoff—minus the pilot!

Flying in the most remote parts of northern Maine presented challenges and surprises. First, the pilot was on his own; no help was available by radio. The weather changed quickly, the snow surface switched from powder to frozen to flooded, and it was often very cold and windy. Plane engines did not start in cold weather unless preheated with a propane burner. Some of the situations we encountered during the first few seasons illustrate the danger.

Super Cub 1473C, survivor of many close calls

Since the water level of Spencer Lake receded in the fall, the plane was tied down on the dry, sizable width of snow-covered, sandy lake bottom. The first winter, we had not constructed permanent buried anchors, so the Super Cub sat in front of our cabin tied on each side to a cluster of three 150-pound propane gas cylinders.

Carl and I went to sleep at dark one night, after a long, exhausting day of reconstruction on the future Hardscrabble. A gentle breeze created a soothing sound as the tall pines’ branches swayed outside.

I woke suddenly when the window next to the bed rattled. Obviously, the wind was blowing harder from the south, a sure sign of approaching bad weather. Quickly, sound sleep returned. Sometime later, a loud creaking noise jolted both Carl and I upright. The building shuddered and shook so violently, I feared for the recently installed new metal roof.

“Jake, we are #$##%#! This gale will wreak havoc!” Carl shouted.

“I know! But I don’t care about the stacks of loose plywood or even the windows we didn’t finish installing— I’m worried about the plane!” I yelled back. “That’s valuable!”

I looked outside. “Holy $##%!” The intense beam of the six volt flashlight illuminated a sickening sight. The Super Cub was dancing. Up it flew— about a foot above the ground, hopping slowly along, and dragging the cylinders. It would pause, then rise up again. It had moved about 100 feet in the direction of several large pine trees outside the door. Carl and I quickly dressed and raced toward the wing tie-down ropes.

Cabin Number Six, one of several at Hardscrabble.

Screaming above the roar of the blow, I yelled, “Pull toward the ice every time it lifts off!”

Two ants could have done just as well. The wind had tremendous power. At that moment I was sure our most important possession was lost.

Soon, we heard a sickening noise. One wing had contacted a tree trunk, and was sliding up and down the bark. We retreated inside, downed a couple shots of bourbon and lay back down. Neither of us slept, our spines rigid with each sharp crack emitted by the structure, and the constant roar. What was going to happen next?

Without planning to, we took turns getting up to look outside. The Super Cub did not change position. By morning the worst was over, but rain fell steadily.

Unbelievably, the only damage was to the wing: an indentation about one foot wide and six inches deep. An airplane wing is designed with inspection holes in the outer surface fitted with covers. After removing several of these, no structural damage was evident. I was confident the plane would fly normally.

When decent weather returned, I took off for Greenville to make temporary repairs. Initially, I flew just over the surface of the ice, in case the damaged wing compromised control. Luckily, it didn’t. The old girl was tough!

The sweet old Taylorcraft BC-85D (BC-65 with a C-85 engine) from the leading photo that Jake cut his teeth on as a pilot.

Chapter 8: A floatplane can transport anything

Thirty or forty years ago, many lakes and ponds in northern Maine lay a long ways from a passable road. Numerous private camps and commercial lodges were located on those bodies of water. Often the residents of those remote areas would undertake projects requiring large volumes of material or freight to be ferried from Greenville to the site. This was when floatplanes saw use as trucks.

Four different types of planes were employed. A DeHavilland Beaver was the biggest, and could haul nearly a ton. That airplane was designed from scratch as a bush workhorse. Cessna 206s, 185s, and 180s, smaller but very capable, made up the rest of the fleet. Although the interior cargo space was adequate for much of the freight, often, bigger items had to be tied to the exterior. Each type of external freight had to be secured in a particular manner. What I’m about to describe was customary forty years ago. Today, the FAA has made it almost impossible to fly external loads.

Jake preparing to fly a large deer out of Roaring Brook pond in the Super Cub.

For lumber, two ropes were tied to the base of the fore and aft float struts. Boards were stacked on top of the ropes on each float, the longest on the bottom. Weight of the increasing load was judged by the water line of the pontoon. Lastly, the ropes were wrapped around the outside of the pile and pulled tight behind each float strut and secured. Most important, a second rope was strung between the first two ropes and cinched tight. This method pulled the front and rear ropes together, using mechanical advantage. The resultant harness was very taut. The plane was spun around at the dock in order to load each float. This could not be accomplished in high winds, nor would it be wise to haul lumber in turbulent conditions.

Propane cylinders were usually moved with the Beaver. Using planks, Five cylinders could be rolled into the cargo area and stacked horizontally. This procedure required a rugged pilot, because each tank weighed about 150 pounds. Many float plane pilots ended up lame, from lifting under cramped conditions. After the interior cylinders were in place, two additional tanks were lashed to each float. We used to fly with the rear doors cracked open for fume ventilation. A door ajar a couple of inches will evacuate a huge volume of air once airborne.

Pilots' choice for canoe-hauling: The De Havilland Beaver.

Freezers, refrigerators, generators, and other heavy, bulky items could be moved on top of a float. Ropes were arranged in a similar fashion as that described for lumber. Also, any convenient attachment point was secured for good measure. The old Beaver looked comical flying along with a big box freezer extending from one side.

Picture windows presented a special challenge. The last thing you needed was for one to shatter on takeoff or in flight. The trick was to invent a way to place the window inside. Often, by removing the front passenger door, the front passenger seat, and the rear seat, a decent-sized frame could be squeezed in. The load would be roped to interior cargo rings. The plane flew well without the door.

The external load that generated the most profit was the canoe. With the designation by the federal government of the Allagash River as a wild, protected stream, demand escalated from canoeists for transportation. The most practical way to reach both ends of the Allagash was by plane. The Beaver made most trips because it could easily haul two canoes and four passengers plus luggage. The canoes were lashed just like a pile of lumber, but an additional short rope held the bow. The adventurers were dropped off at Churchill Dam and picked up in the St. Francis River.

It's hard to beat a Skywagon for practical hauling on floats.

When Beth and I bought Hardscrabble, we had to settle for a smaller floatplane. I continued to move tons of freight, but more trips were required than at Folsom’s. Most cargo was kitchen staples— case after case of canned vegetables, pie fillings, flour, sugar, etc. We started making trips in the late winter when daytime temperatures were regularly above freezing. Items easily damaged by cold nights were stored in the root cellar.

In late winter, Spencer Lake would still have thick ice everywhere except the last 100 feet before the shoreline. This was because the melting snow raised the lake level and created open water. The method we found most efficient was to stop the plane 500 feet from shore and load the staples into a 14 foot boat. We’d push the boat over the slick ice, ready to jump aboard when the bow broke through. Usually the boat had enough momentum to coast to the beach, so we could unload.

Jake and Carl flew this Aeronca Sedan from Virginia back to Hardscrabble.

Once I got a sudden surprise. Pushing on the stern, I stepped into an ice-fishing hole that had been enlarged by the melt. In an instant, I was holding onto the boat, submerged to my armpits. The shock was so great that I struggled for breath.

Memories of Harscrabble: daughter Thea proudly displaying her catch

With a helping hand from Carl, I popped back up on the ice. Fortunately, a warm cabin was nearby.

Obviously, these all-day hauling episodes required a big crew. In addition to a pilot, loaders in town and unloaders at Hardscrabble were necessary. Our friends always volunteered for the task, and a party atmosphere was the norm. Once the ice melted we moved more perishable goods by floatplane. That exercise seemed a breeze, compared to the earlier efforts.

Hunting trophies always rode on the floats. A slice was made in the hide behind the tough sinew at the deer’s knee, enabling the rope to pass through. With the knees secured high on the float struts, the animal could not move. During November, the air was often well below freezing while the water temperature was above 32. As a result, ice formed over the surface of the floats on every takeoff. The deer blood, frozen into that ice, colored the floats red during the season.

The squeamish reader may want to end the chapter here.

People died and were killed in the woods. Sometimes the only way to evacuate the body was by floatplane. A medical examiner was flown in and accompanied the body out. During hunting season, heart attacks claimed some sports. On occasion, several days went by before the body was found. If the temperature was low enough, the deceased was frozen rock-solid, often into an unnatural shape. The only possible way to move such a body by floatplane was tied to a float.

Dick Folsom told a story that occurred before I was hired. One busy Saturday, the pilots were busy flying hunters and their trophies. A small crowd had gathered around the docks to admire some of the larger deer. By coincidence, Dick had been asked to fly a frozen body. As he flew above town 1,000 feet high, several people noticed the unusually large buck tied to the floats. Soon the crowd swelled. When he landed and taxied toward the dock people began to scatter. Dick said some were literally running away! Some folks may enjoy watching horror movies, but no one likes to feel like they’re in one!

Jake and Beth's retirement home and airstrip, Morrel Field, outside Sangerville, Maine.

Review written by Zane Jacobson - September 28th, 2016 - Originally published on www.backcountrypilot.org